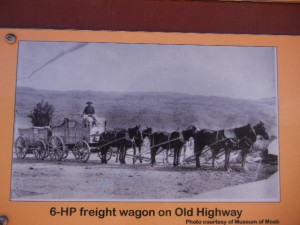

29 May: Kyle headed home, while Lowry and Corwyn stayed to camp a few more days with us. We relocated to Dead Horse Point State Park in Utah, near Canyonlands National Park. The plateau here goes out to a point separated from the main part of the plateau by a very narrow neck. Ranchers used to corral wild mustangs by driving them out onto the point and trapping the herd out there with a fence across the neck. The story goes that after the herders had taken the horses that they wanted, they neglected to release the others and they died out on the point, hence the park’s name. We went for a short walk along the rim at the tip of the point, where the view was breathtaking. The Colorado River far below follows a tightly winding course of “entrenched meanders.” Typically, a river deviates from a fairly direct course to meander back and forth only in the nearly flat floodplain near the river mouth. What happened here, however, is that the Colorado developed meanders a very long time ago, then geological uplift tilted the land, increasing the river gradient. The increased river current eroded deeper into the plateau in the streambed that had already been established.

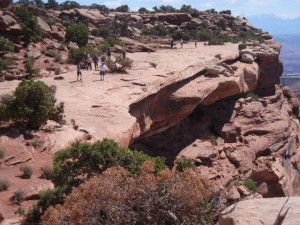

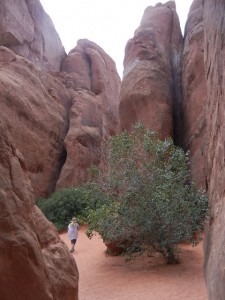

30 May: Canyonlands National Park is centered on the confluence of the Green River and the Colorado River, both of which have cut very deep and steep canyons into the plateau, isolating the three sections of the park from each other. We visited the northern section, between the two rivers before they join (“the Island in the Sky”). We hiked a very enjoyable trail from the observation point at the end of the road, west to an overlook of the Green River valley and back. The trail follows the rim of the plateau, with constant overlooks of another plateau far below, into which the rivers have cut deep canyons. Generally, the rock strata of the broad region known as the Colorado Plateau (western Colorado and most of Utah) are nearly horizontal, and have not undergone much faulting, folding, or tilting. These sedimentary layers differ in color depending on changes in the climatic conditions over the millions of years when they were deposited (inland seas, sand dunes, floodplains, freshwater swamps, etc.). This produced horizontal bands of various shades of reddish brown, gray, and white sandstone and shale that are visible for hundreds of miles in this wide open landscape.